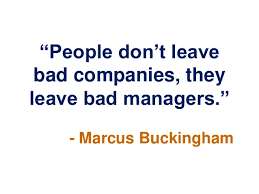

Compelling research shows that people most often leave their manager, not the company. I spent almost two years solely dedicated to researching the topic of employee retention. I served on a one-person task force with a mission to “fix the attrition problem” we were having in our department of over two thousand people. As a call center, high voluntary turnover is somewhat expected, but my research found far too many easy ways to keep people. I invested a significant amount of time with management in the ten different sites in which we worked at the time. The goal was to ensure that I understood the root causes, and they understood the potential countermeasures to retain their people. It was clear that some managers needed to truly understand how delicate their relationships were with the people they worked with and how easily we lost good people. As an immature manager in my earlier days, I could empathize with a lack of understanding of the criticality of a strong bond.

Compelling research shows that people most often leave their manager, not the company. I spent almost two years solely dedicated to researching the topic of employee retention. I served on a one-person task force with a mission to “fix the attrition problem” we were having in our department of over two thousand people. As a call center, high voluntary turnover is somewhat expected, but my research found far too many easy ways to keep people. I invested a significant amount of time with management in the ten different sites in which we worked at the time. The goal was to ensure that I understood the root causes, and they understood the potential countermeasures to retain their people. It was clear that some managers needed to truly understand how delicate their relationships were with the people they worked with and how easily we lost good people. As an immature manager in my earlier days, I could empathize with a lack of understanding of the criticality of a strong bond.

Sometimes, managers of the people on the front line who deal directly with customers, for example, look only at their immediate team. If someone leaves, it’s no big deal—they will get someone new and move on. Outside of the investment expense and effort to retrain, however, we are at risk of losing the knowledge a person leaving had, and, worse, are allowing many of these great people to potentially move on to a competitor.

According to Leigh Branham in the book The 7 Hidden Reasons Employees Leave, she writes, “89% of managers said they believe that employees leave and stay mostly for the money. Yet, my own research, along with Saratoga Institute’s surveys of almost 20,000 workers… and the research of dozens of other studies, reveal that actually, 80 to 90 percent of employees leave for reasons related NOT to money, but to the job, the manager, the culture, or the work environment.” Beverly Kaye and Sharon Jordan-Evans stated in the book, Love ’Em or Lose ’Em that, “A 25-year-long Gallup Organization study based on interviews with 12-million workers at 7,000 companies also found that the relationship with a manager largely determines the length of an employee’s stay.” Both references clearly indicate how much impact a manager has on retaining an employee.

During my research, I found that employees typically don’t leave over an event, but add up multiple “little” events prior to making the decision to go. An employee may claim she left over a performance appraisal score, but it was most likely just the straw that broke the camel’s back. She was most likely formulating thoughts to leave long before that discussion. The decision to leave typically festers over time as people gradually change their thoughts of leaving into taking action. The time it takes varies from days to weeks to months and is contingent on many factors, including the economy, the presence of a reliable back-up plan, and the employee’s tolerance level with what is going on.

The employee often disengages from work responsibilities, culture, and management. This disengagement time frame will vary based on the severity of what the employee is up against, both personally and professionally. The responsibility clearly resides with the manager to identify the warning signs as far in advance as possible prior to a person making the commitment to communicate his or her intentions to leave. Once that announcement is made, it is most likely too late to save them. This is a key factor in knowing the people you work with and knowing when to intervene.

The organization has the obligation to invest the time and make the effort to save people who want to be there (and are performing or have the potential to perform). They obviously were good enough to hire, and deserve the effort. Sometimes, the person may just be in the wrong position. How many managers are willing to invest the time to find the right fit in the company? As an inexperienced leader, I remember saying, “Who needs that person anyway?” The company does. I have heartburn every time I think of the number of potential people who left the company on my account. I don’t think the number is too large, but anything more than zero is too many.

Once, a young woman said to me that she was having personal issues and needed to talk. I said that I would be glad to talk after I got back from my meeting. She said it was important, but I chose not to listen. When I got back from the meeting—which was not very important—the person quit, and I never heard from her again. She had been a consistent performer and needed someone to listen to her issues. I saw the obvious sign but did not attach the appropriate urgency to it. I’m sure a couple of minutes could have saved her.

I vowed to never let that happen again. A couple of years later, I received a message that a woman who had worked for me for a short period of time had quit without notice. She had come in to let us know and had already left. I took a chance and ran down to the Human Resources office and found she was wrapping up with them. I asked for a couple of minutes with her—a couple of minutes I could not have bothered with years earlier when I chose to ignore another pleading person. We spoke for a while. She was having personal issues at home and also felt she lacked the appropriate support at work since she was only an average performer. I knew she could perform well if she was focused. I asked her to go home and commit to coming back the next day, and we would work out a plan together. The honest and mutually direct conversation built a bond that grew as time went on. She became a consistent performer and eventually moved on to another line of business in which she became a top performer. I see her in the halls every once in a while and I burst with pride. I am proud of her staying with the company for an additional twelve years and still going. I am proud that I refused to allow my stubbornness, at the time, to allow her to leave. She was good for the company then and is great for the company now. I just didn’t know how much at the time.

Whether it is moving the person to another area, moving them to another manager, or working on building the relationship between yourself or an employee, the tough part is being attentive enough to see the signs and courageous enough to take action to save them. It is too easy to say he or she is just having a bad day and we’ll talk later or, worse, we’ll get another good person. Before you say, “Oh, well, ” you might want to first contact the people who need to invest in the recruiting to get them, the trainers who will teach them, and all of their new surrounding teammates who will invest time in bringing them up the learning curve. Make the effort to retain and save good people. The relationship between managers and employees is critical to everyone’s success.

Thomas B. Dowd III’s books available in softcover, eBook, and audiobook (From Fear to Success only):

- Now What? The Ultimate Graduation Gift for Professional Success

- Time Management Manifesto: Expert Strategies to Create an Effective Work/Life Balance

- Displacement Day: When My Job was Looking for a Job…A Reference Guide to Finding Work

- The Transformation of a Doubting Thomas: Growing from a Cynic to a Professional in the Corporate World

- From Fear to Success: A Practical Public-speaking Guide received the Gold Medal at the 2013 Axiom Business Book Awards in Business Reference

- The Unofficial Guide to Fatherhood

See “Products” for details on www.transformationtom.com. Book, eBook, and audiobook (From Fear to Success only) purchase options are also available on Amazon- Please click the link to be re-directed: Amazon.com